Critical race theory is the idea that racism is systematic in the nation’s institutions, specifically maintaining the dominance of white people, according to the 57th Edition Associated Press Stylebook.

Gov. Jeff Landry signed an executive order on Aug. 12, 2024, titled, “Preventing the use of critical race theory in Louisiana’s K-12 public education system.” He issued the following statement in a press release regarding his decision:

“This executive order is a much-needed sigh of relief for parents and students across our state, especially as kids are heading back to school. Teaching children that they are currently or destined to be oppressed or to be an oppressor based on their race and origin is wrong and has no place in our Louisiana classrooms. I am confident that under Dr. Brumley’s leadership our education system will continue to head in the right direction, prioritizing American values and common-sense teachings.”

According to the AP Stylebook, critical race theory is not a fixture of K-12 education but has become a catch-all political term for any teaching in schools about race and American history. “Some people take issue with how schools have addressed diversity and inclusion,” the book’s entry on race states.

Louisiana is one of 44 states that have introduced bills or made steps to restrict teaching critical race theory in public education, according to Education Week.

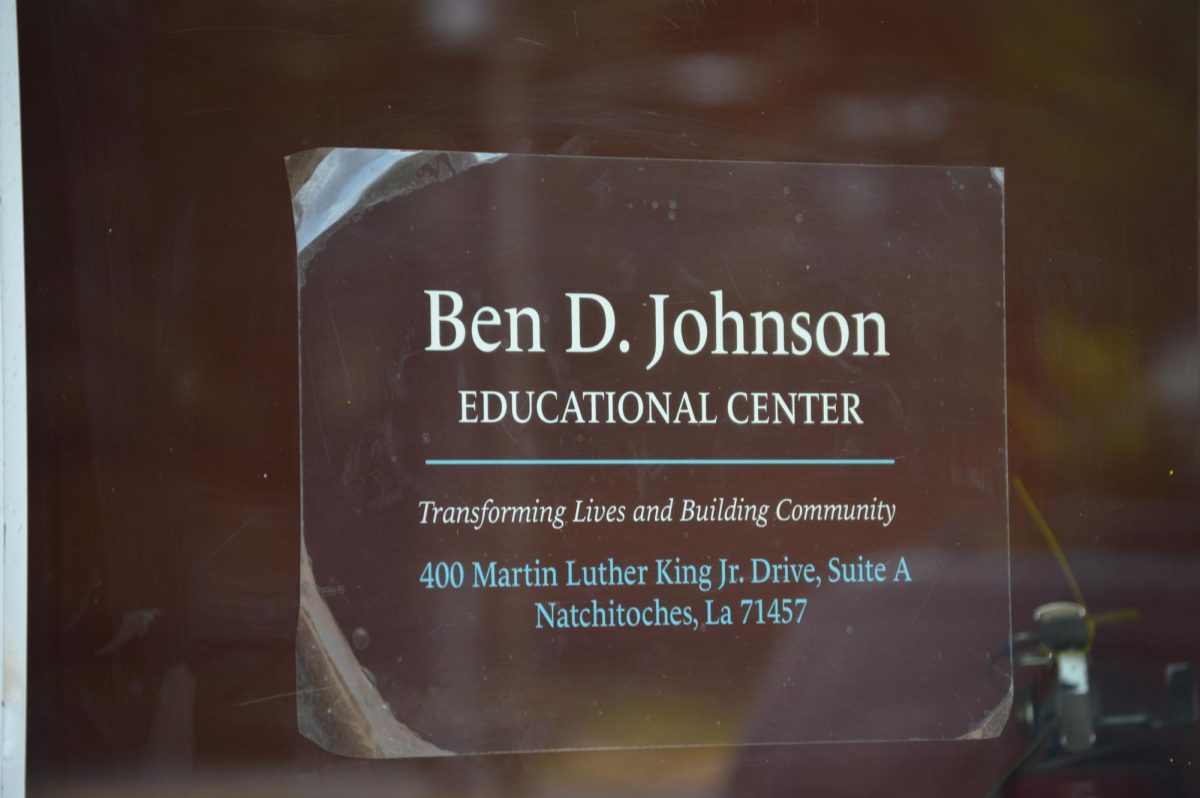

Jasmine Wise, professor and coordinator of Black Studies and for the Gail Jones Metoyer Center for Inclusion and Diversity at NSU, explained that critical race theory is misunderstood because of the political connections created in the past few years.

“Like most things in America, if something is misunderstood, we begin to make our own definitions. The misunderstanding of CRT is problematic in that people create narratives that can be divisive instead of taking the time to understand the facts,” Wise said.

When it comes to the teaching of critical race theory, Wise explained that it would be beneficial for some high school courses such as Civics, English, World History and American History.

“I don’t know if I believe there should be a course dedicated to critical race theory but there should be mention where it naturally fits,” Wise said.

Rebecca Riall, assistant professor and coordinator of Pre-Law and Paralegal Studies and American Indian and Indigenous Studies at NSU, explained that teaching truthful information about history and society, including critical race theory when applied, and giving students tools to critically evaluate what they hear is crucial to having well-rounded citizens.

“We don’t gain anything by teaching history if we aren’t teaching history that is accurate, valid and incorporates experiences of different people. In anthropology, societies are seen as developing as they do because of historical contingencies. We don’t understand where society is today if we don’t understand those,” Riall said.

Riall doesn’t think guilt is the message of talking openly about society. She believes that history without the ugly parts is a dishonest fantasy and that people can learn from history to be proud of not having prejudices against one another.

“Whether we like it or not, race, even though it’s not biologically real, is something that is very pervasive in our society. My experience is that students, regardless of their identity, find it empowering to learn about struggles that are common to many groups and how people throughout American history have stood up for justice and equality. That is the best part of America,” Riall said.

While the connotations of Critical Race Theory often prompt a stop on the conversation of race and its history, Wise and Riall explained that teaching the realities and harshness of history can ignite a more fluid and open conversation for all on race.